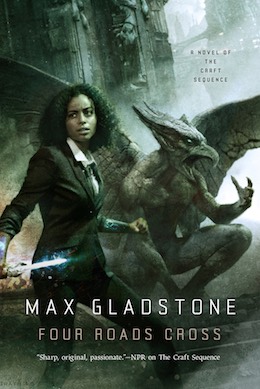

We’re excited to bring you four days of Four Roads Cross, the fifth book in Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence! Read chapters 2 and 3 below, or head back to the beginning with chapter 1!. Four Roads Cross publishes July 26th from Tor Books.

The great city of Alt Coulumb is in crisis. The moon goddess Seril, long thought dead, is back—and the people of Alt Coulumb aren’t happy. Protests rock the city, and Kos Everburning’s creditors attempt a hostile takeover of the fire god’s church. Tara Abernathy, the god’s in-house Craftswoman, must defend the church against the world’s fiercest necromantic firm—and against her old classmate, a rising star in the Craftwork world.

As if that weren’t enough, Cat and Raz, supporting characters from Three Parts Dead, are back too, fighting monster pirates; skeleton kings drink frozen cocktails, defying several principles of anatomy; jails, hospitals, and temples are broken into and out of; choirs of flame sing over Alt Coulumb; demons pose significant problems; a farmers’ market proves more important to world affairs than seems likely; doctors of theology strike back; Monk-Technician Abelard performs several miracles; The Rats! play Walsh’s Place; and dragons give almost-helpful counsel.

2

Stone wings shook Alt Coulumb’s nights, and godsilver shone from its shadows.

Gavriel Jones fled through garbage juice puddles down a narrow alley, panting tainted humid air. Dirty water stained the cuffs of her slacks and the hem of her long coat; behind, she heard the muggers’ running feet.

They did not shout after her. No breath was wasted now. She ran and they pursued.

Dumb, dumb, dumb, was the mantra her mind made from the rhythm of her run. She’d broken the oldest rules of city life. Don’t walk through the Hot Town alone after midnight. Don’t mix white wine with red meat, look both ways before you cross, never step on cracks. And always, always give them your purse when they ask.

She ran deeper into the Hot Town, beneath high shuttered windows and blank brick walls scarred by age and claw. She cried out, her voice already ragged. A window slammed.

Above, a full moon watched the chase. Ahead, the alley opened onto a broad, empty street. Beneath the sour-sweet stink of rot, she smelled spiced lamb. Someone was selling skewers on the corner. They might help her.

She glanced back. Two men. Three had approached her when she ducked into the alley for a cigarette. Where was the third?

She slammed into a wall of meat. Thick arms pulled her against a coat that smelled of tobacco spit and sweat. She kneed him in the groin; he pulled his crotch out of reach, hissed, threw her. Gabby slammed to the ground and splashed in a scummy puddle.

She kicked at his knee, hard but too low: the steel toe of her boot slammed into his shin but didn’t break his kneecap. He fell onto her, hands tangled in her clothes, her hair. She hit his nose with the crown of her head, heard a crunch. He was too far gone on whatever dust propelled him to feel pain. He bled onto her face; she jerked her head aside and pressed her lips closed, don’t get any in your mouth don’t get any in your mouth—

The others caught up.

Strong hands tore the purse from her, and she felt her soul go with it. They tossed her life between them. The boot came next, its fi rst hit almost delicate, a concertmistress drawing a fresh-strung bow across clean strings. Still hurt, though. She doubled around the leather, and gasped for air that didn’t reach her lungs.

His second kick broke her rib. She hadn’t broken a bone in a long time, and the snap surprised her. Bile welled in the back of her throat.

She pulled her hands free, clawed, found skin, drew more blood. The boot came again.

Still, up there, the moon watched.

Gabby lived in a godly city, but she had no faith herself.

Nor did she have faith now. She had need.

So she prayed as she had been taught by women in Hot Town and the Westerlings, who woke one day with echoes in their mind, words they’d heard cave mouths speak in dreams.

Mother, help me. Mother, know me. Mother, hold and harbor me.

Her nails tore her palms.

Hear my words, my cry of faith. Take my blood, proof of my need.

The last word was broken by another kick. They tried to stomp on her hand; she pulled it back with the speed of terror. She caught one man’s leg by the ankle and tugged. He fell, scrabbled free of her, rose cursing. A blade flashed in his hand.

The moon blinked out, and Gabby heard the beat of mighty wings.

A shadow fell from the sky to strike the alley stones so hard Gabby felt the impact in her lungs and in her broken rib. She screamed from the pain. Her scream fell on silence.

The three who held and hit her stopped.

They turned to face the thing the goddess sent.

Stone Men, some called them as a curse, but this was no man. Back to the streetlights at the alley’s mouth, face to the moon, she was silhouette and silver at once, broad and strong, blunt faced as a tiger, long toothed and sickle clawed with gem eyes green and glistening. Peaked wings capped the mountain range of her shoulders. A circlet gleamed upon her brow.

“Run,” the gargoyle said.

The man with the knife obeyed, though not the way the gargoyle meant. He ran forward and stabbed low. The gargoyle let the blade hit her. It drew sparks from her granite skin.

She struck him with the back of her hand, as if shooing a fly, and he flew into a wall. Gabby heard several loud cracks. He lay limp and twisted as a tossed banana peel.

The other two tried to run.

The gargoyle’s wings flared. She moved like a cloud across the moon to cut off their retreat. Claws flashed, caught throats, and lifted with the gentleness of strength. The men had seemed enormous as they chased Gabby and hit her; they were kittens in the gargoyle’s hands. Gabby pressed herself up off the ground, and for all the pain in her side she felt a moment’s compassion. Who were these men? What brought them here?

The gargoyle drew the muggers close to her mouth. Gabby heard her voice clear as snapping stone.

“You have done wrong,” the gargoyle said. “I set the Lady’s mark on you.”

She tightened her grip, just until the blood flowed. The man on the left screamed; the man on the right did not. Where her claws bit their necks, they left tracks of silver light. She let the men fall, and they hit the ground hard and heavy. She knelt between them. “Your friend needs a doctor. Bring him to Consecration and they will care for him, and you. The Lady watches all. We will know if you fail yourself again.”

She touched each one on his upper arm. To the gargoyle it seemed no more consequential than a touch: a tightening of thumb and forefinger as if plucking a flower petal. The sound of breaking bone was loud and clean, and no less sickening for that.

They both screamed, this time, and after—rolling on the pavement filth, cradling their arms.

The gargoyle stood. “Bear him with the arms you still have whole. The Lady is merciful, and I am her servant.” She delivered the last sentence flat, which hinted what she might have done to them if not for the Lady’s mercy and her own obedience. “Go.”

They went, limping, lurching, bearing their broken friend between them. His head lolled from side to side. Silver glimmered from the wounds on their necks.

And, too, from scars on the alley walls. Not every mark there glowed—only the deep clean grooves that ran from rooftops to paving stones, crosshatch furrows merging to elegant long lines, flanked here by a diacritical mark and there by a claw’s flourish.

Poetry burned on the brick.

The gargoyle approached. Her steps resounded through the paving stones. She bent and extended a heavy clawed hand. Gabby’s fingers fit inside the gargoyle’s palm, and she remembered a childhood fall into the surf back out west, how her mother’s hand swallowed hers as she helped her stand. The gargoyle steadied Gabby as she rose. At full height, Gabby’s forehead was level with the gargoyle’s carved collarbone. The gargoyle was naked, though that word was wrong. Things naked were exposed: the naked truth in the morning news, the naked body under a surgeon’s lights, the naked blossom before the frost. The gargoyle was bare as the ocean’s skin or a mountainside.

Gabby looked into the green stone eyes. “Thank you,” she said, and prayed too, addressing the will that sent the being before her: Thank you. “The stories are true, then. You’re back.”

“I know you,” the gargoyle replied. “Gavriel Jones. You are a journalist. I have heard you sing.”

She felt an answer, too, from that distant will, a feeling rather than a voice: a full moon over the lake of her soul, the breath of the mother her mother had been before she took to drink. “You know who I am and saved me anyway.”

“I am Aev,” she said, “and because I am, I was offered a choice. I thought to let you pay for your presumption. But that is not why we were made.”

“I know.” The pain in her chest had nothing to do with the broken rib. She turned away from the mass of Aev. “You want my loyalty, I guess. A promise I won’t report this. That I’ll protect and serve you, like a serial hero’s sidekick.”

Aev did not answer.

“Say something, dammit.” Gabby’s hands shook. She drew a pack of cigarettes from her inside pocket, lit one. Her fingers slipped on the lighter’s cheap toothed wheel. She breathed tar into the pain in her side.

When she’d drawn a quarter of the cigarette to ash, she turned back to find the alley empty. The poems afterglowed down to darkness, like tired fireflies. A shadow crossed the moon. She did not look up.

The light died and the words once more seemed damaged.

She limped from the alley to the street. A wiry-haired man fanned a tin box of coals topped by a grill on which lay skewers of seasoned lamb.

Gabby paid him a few thaums of her soul for a fistful of skewers she ate one at a time as she walked down the well-lit street past porn shop windows and never-shut convenience stores. The air smelled sweeter here, enriched by cigarette smoke and the sharp, broad spices of the lamb. After she ate, even she could barely notice the tremor in her hands. The drumbeat of blood through her body faded.

She tossed the skewers in a trash can and lit a second cigarette, number two of the five she’d allow herself today. Words danced in.side her skull. She had promised nothing.

She realized she was humming, a slow, sad melody she’d never heard before that meandered through the C-minor pentatonic scale, some god’s or muse’s gift. She followed it.

Her watch chimed one. Still time to file for matins, if she kept the patter simple.

3

Tara was buying eggs in the Paupers’ Quarter market when she heard the dreaded song.

She lived three blocks over and one north, in a walk-up apartment recommended by the cheap rent as well as by its proximity to the Court of Craft and the market itself, Alt Coulumb’s best source of fresh produce. Now, just past dawn, the market boiled with porters and delivery trucks and human beings. Shoppers milled under awnings of heavy patterned cloth down mazed alleys between lettuce walls and melon pyramids.

As she shouldered through the crowd, she worried over her student loans and her to-do list. The Iskari Defense Ministry wanted stronger guarantees of divine support from the Church of Kos, which they wouldn’t get, since a weaker version of those same guarantees had almost killed Kos Himself last year. The Iskari threatened a breach of contract suit, ridiculous—Kos performed his obligations flawlessly. But she had to prove that, which meant another deep trawl of church archives and another late night.

Which wouldn’t have felt like such a chore if Tara still billed by the hour. These days, less sleep only meant less sleep. She’d sold herself on the benefits of public service: be more than just another hired sword. Devote your life to building worlds rather than tearing them down. The nobility of the position seemed less clear when you were making just enough to trigger your student loans but not enough to pay them back.

Life would feel simpler after breakfast.

But when she reached the stall where Matthew Adorne sold eggs, she found it untended. The eggs remained, stacked in bamboo cartons and arranged from small to large and light to dark, but Adorne himself was gone. Tara would have been less surprised to find Kos the Everburning’s inner sanctum untended and his Eternal Flame at ebb than she was to see Adorne’s stand empty.

Nor was his the only one.

Around her, customers grumbled in long lines. The elders of the market had left assistants to mind their booths. Capistano’s boy scrambled behind the butcher’s counter, panicked, doing his father’s work and his at once. He chopped, he collected coins with bits of soul wound up inside, he shouted at an irate customer carrying a purse three sizes too large. The blond young women who sold fresh vegetables next to Adorne, the stand Tara never visited because their father assumed she was foreign and talked to her loud and slow as if she were the only dark-skinned woman in Alt Coulumb, they darted from task to task, the youngest fumbling change and dropping onions and getting in the others’ way like a summer associate given actual work.

Adorne had no assistant. His children were too good for the trade, he said. School for them. So the stall was empty.

She wasn’t tall enough to peer over the crowd, and here in Alt Coulumb she couldn’t fly. A wooden crate lay abandoned by the girls’ stall. Tara climbed the crate and, teetering, scanned the market.

At the crowd’s edge she saw Adorne’s broad shoulders, and tall, gaunt Capistano like an ill-made scarecrow. Other stall-keepers, too, watched—no, listened. Crier’s orange flashed on the dais.

Adorne remained in place as Tara fought toward him. Not that this was unusual: the man was so big he needed more cause to move than other people. The world was something that happened to black-bearded Matthew Adorne, and when it was done happening, he remained.

But no one else had moved either.

“What’s happened?” Tara asked Adorne. Even on tiptoe, she could barely see the Crier, a middle-aged, round-faced woman wearing an orange jacket and a brown hat, an orange press pass protruding from the band. Tara’s words climbed the mounds of Adorne’s arms and the swells of his shoulders until they reached his ears, which twitched. He peered down at her through layers of cheek and beard—raised one tree-branch finger to his lips.

“Encore’s coming.”

Which shut Tara up fast. Criers sang the dawn song once for free, and a second time only if the first yielded sufficient tips. An encore meant big news.

The Crier was an alto with good carry, little vibrato, strong belt. One thing Tara had to say for the archaic process of Alt Coulumbite news delivery: in the last year she’d become a much better music critic.

Still, by now a newspaper would have given her a headline reason for the fuss.

The song of Gavriel Jones, the Crier sang.

Tells of a New Presence in our Skies.

Oh, Tara thought.

Hot Town nights burn silver

And Stone Men soar in the sky

Pray to the moon, dreams say

And they’ll spread their wings to fly.

A tale’s but a tale ’til it’s seen

And rumors do tend to spin

I saw them myself in the Hot Town last night

Though telling, I know I sin.

Tara listened with half an ear to the rest of the verse and watched the crowd. Heads shook. Lips turned down. Arms crossed. Matthew Adorne tapped his thick fingers against his thicker biceps.

Seril’s children were playing vigilante. A Crier had seen them.

The song rolled on, to tell of gargoyles returned to Alt Coulumb not to raid, as they had many times since their Lady died in the God Wars, but to remain and rebuild the cult of their slain goddess, Seril of the moon, whom Alt Coulumb’s people called traitor, murderer, thief.

Tara knew better: Seril never died. Her children were not traitors. They were soldiers, killers sometimes in self-defense and extremity, but never murderers or thieves. To the Crier’s credit, she claimed none of these things, but neither did she correct popular misconceptions.

The city knew.

How would they respond?

There was no Craft to read minds without breaking them, no magic to hear another’s thoughts without consent. Consciousness was a strange small structure, fragile as a rabbit’s spine, and it broke if gripped too tightly. But there were more prosaic tricks to reading men and women—and the Hidden Schools that taught Tara to raise the dead and send them shambling to do her bidding, to stop her enemies’ hearts and whisper through their nightmares, to fly and call lightning and steal a likely witness’s face, to summon demons and execute contracts and bill in tenths of an hour, also taught her such prosaic tricks to complement true sorcery.

The crowd teetered between fear and rage. They whispered: the sound of rain, and of thunder far away.

“Bad,” Matthew Adorne said in as soft a voice as he could make his. “Stone Men in the city. You help the priests, don’t you?”

Tara didn’t remember the last time she heard Matthew Adorne ask a question.

“I do,” Tara said.

“They should do something.”

“I’ll ask.”

“Could be one of yours,” he said, knowing enough to say “Craftsman” but not wanting, Tara thought, to admit that a woman he knew, a faithful customer, no less, belonged to that suspect class. “Scheming. Bringing dead things back.”

“I don’t think so.”

“The Blacksuits will get them,” Adorne said. “And Justice, too.”

“Maybe,” she said. “Excuse me, Matt. I have work.”

So much for breakfast.

Excerpted from Four Roads Cross © Max Gladstone, 2016